Sandra Knispel | Communications Specialist

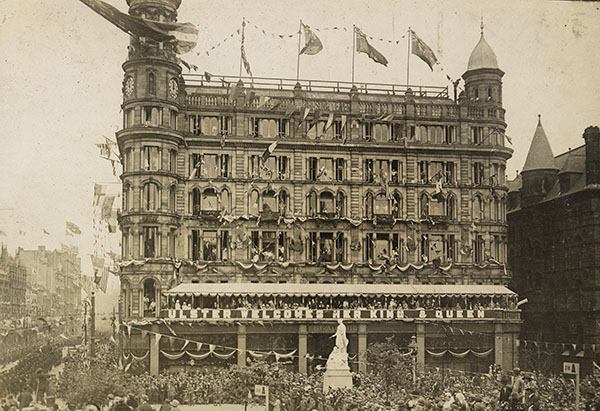

May 10, 2021Drivers stop at the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland on the road from Belfast to Dublin, c. 1950. The partition of Ireland, which became effective in May 1921, was not intended to remain in place for long. (Getty Images photo)

The year 2021 marks 100 years since the Government of the United Kingdom and Ireland divided the Emerald Isle into two self-governing political entities—Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland—under the Government of Ireland Act. What was intended as a temporary solution in the face of unrest, violence, and rebellion is still in effect a century later, as Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

According to Stewart Weaver, a professor of history at the University of Rochester, over time both sides developed two very different and incompatible conceptions of what it means to be Irish: One Catholic, republican, and nationalist, and the other Protestant, loyalist, and unionist. “Of course, they’re all Irish, but they just have fundamentally different conceptions of what that means,” says Weaver. “Conflicted meanings, ultimately, lie at the deepest roots of Ireland’s partition.”

A recipient of the University of Rochester’s 2021 Edward Peck Curtis Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, Weaver teaches about the partition of Ireland as part of his course Great Britain and Ireland since 1800.

WEAVER: Northern Ireland is made up of six of the nine counties of the traditional Irish region of Ulster. This is where I start on the topic of Irish partition in my course. Ulster has always been, in some ways, culturally distinct from the rest of Ireland, even before the Protestant Reformation. Ironically, it was in some ways the most Gaelic of Irish regions; before and after the Reformation it was the most resistant to English rule, which is ironic considering that Ulster is now the most loyalist, unionist region of Ireland.

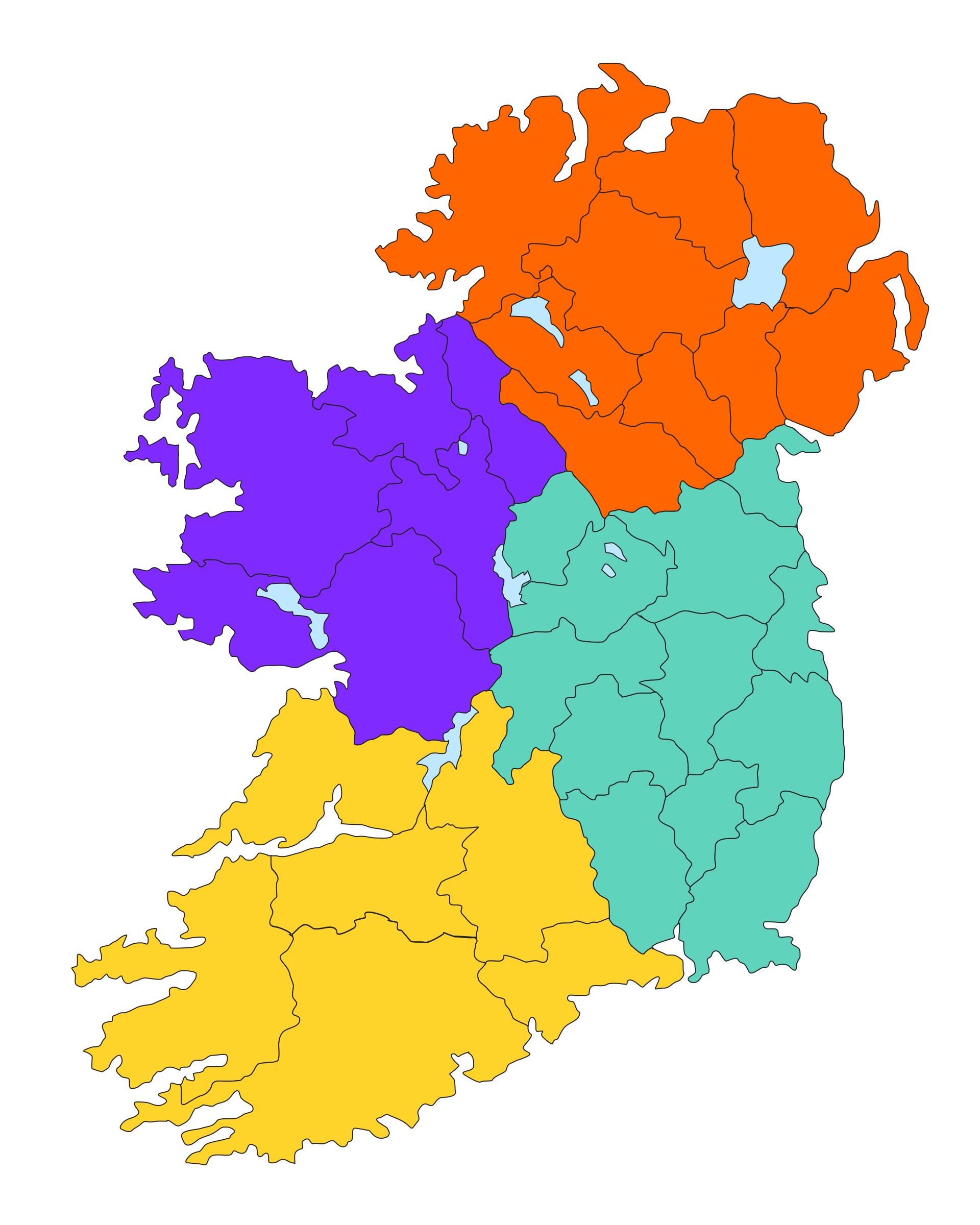

Four Provinces

Ireland—the island made up of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland—includes four traditional regions, or “provinces”: Ulster in the north, Munster in the south, Leinster in the east, and Connaught in the west. They have no legal status today, but share distinct histories and identities.

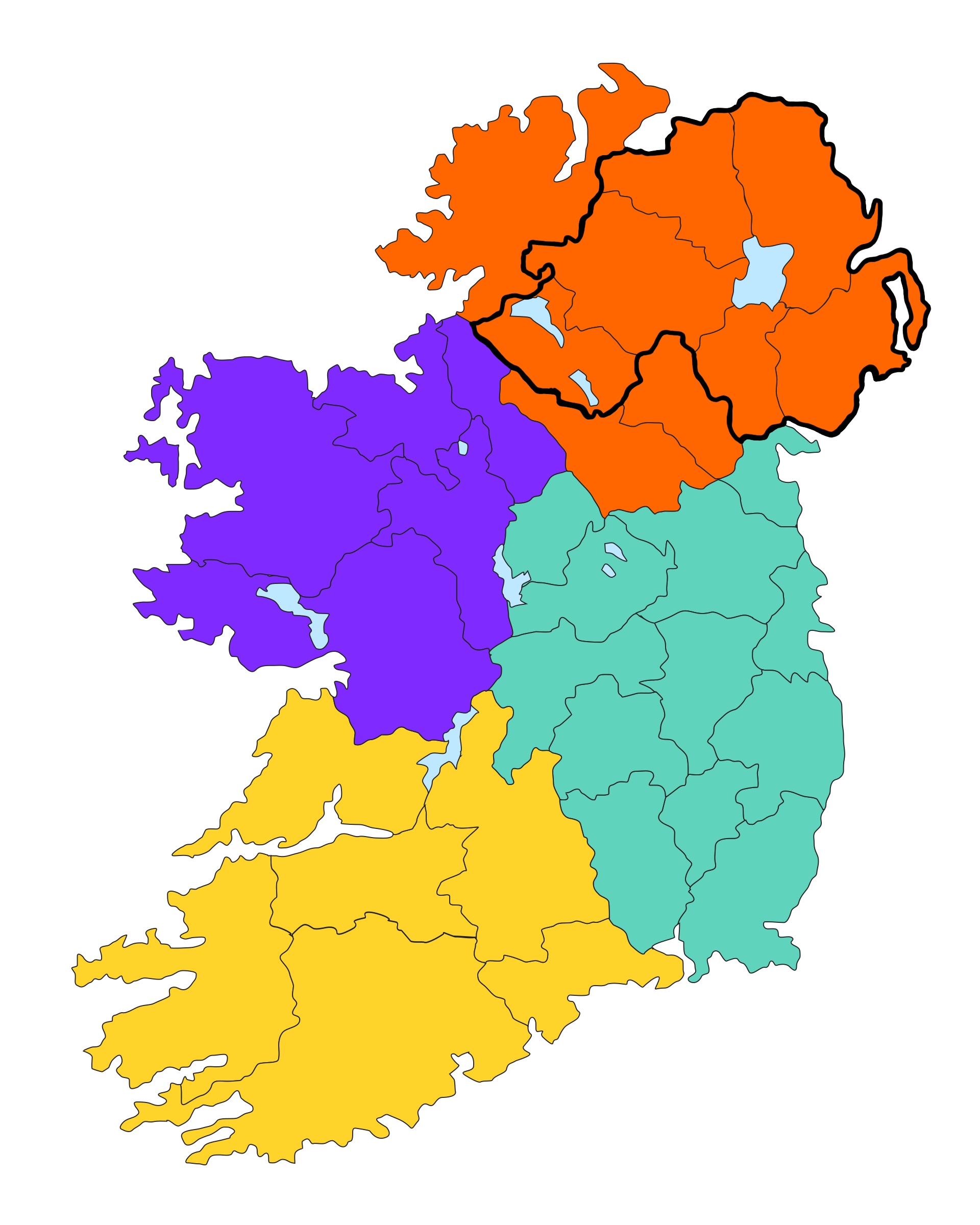

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland, outlined in black, is made up of six counties of the nine-county region of Ulster. The exclusion of the three counties, which had nationalist majorities, ensured a unionist majority in Northern Ireland—but also a large nationalist minority. (The original map posted on May 10, 2021 inaccurately drew the boundary of Northern Ireland. A corrected map was posted on September 24, 2021. We apologize for the error.)

The whole conflict that led to partition reduces fundamentally to the failure of the Reformation in Ireland and the fact that it threw up a confessional divide between the British generally: between the English, the Welsh, the Scots—and the Irish, who remained largely Catholic.

WEAVER: The event known as the Flight of the Earls—when Gaelic lords of Ulster fled in 1607—left the region open and vulnerable to English and Scottish settlement. Under the Stuart monarchs, starting with James I, land ownership in Ulster was transferred from native Ulster Catholics to mostly Scottish Presbyterians, as well as some English Protestants, over the course of the 17th century. It’s true that most of Ireland was occupied and to varying degrees planted and seized by British landowners and aristocrats over the course of the 17th century. But in the south, it was mostly English Anglican Protestants who had a lot more in common with Catholicism, and with the Catholic peasantry, than did these Calvinist Presbyterians of Ulster.

So that made Ulster culturally and confessionally distinct. And the Irish problem arose over the course of the modern period because, in the post-Enlightenment period in the 19th century, there was an intensification of Ireland’s Catholic identity, especially after the famine, and a deepening of Catholicism and of Irish consciousness and Irish political identity. At the same time, even though the north of Ireland was majority Protestant, they too had come to think of themselves as Irish. All of these factors hardened Protestant suspicion in the north and their reluctance to be drawn into an independent Ireland in the south.

WEAVER: The war intensely complicated the situation. Most of Ireland at the outbreak of war in 1914 remained loyal to the United Kingdom. Indeed, the British Army successfully raised Irish regiments for the war on the Western Front in Europe. So it’s not true that Ireland, in general, chose this moment to rebel.

But the Easter Rebels did. This was the Easter Rising—famously the moment in 1916 when the most intransigent, the most committed, the most culturally Republican and Catholic nationalists chose to rise up in Dublin in rebellion against British rule. (The original version of this story posted on May 10, 2021, referred to “English rule” during World War I. It was corrected on January 20, 2022, to read “British rule.” We apologize for the error.)

Their subsequent execution and martyrdom intensely complicated the situation. In the south, the once-unpopular Easter rebels immediately became national heroes. But in the north, their rebellion was regarded as a profound act of betrayal against Great Britain in its time of desperate need, and it heightened the resolve of protestants—who, of course, had been deeply loyal to the United Kingdom during World War I—not to be drawn into a united and independent Ireland. The First World War led to bitter resentment against Irish republicanism in both Britain and Ulster and it made reconciliation between Ireland’s Catholic and Protestant communities impossible in the aftermath of the war. It’s no coincidence that the partition happened in the immediate aftermath of the war.

WEAVER: The Government of Ireland Act was designed to create two separate Home Rule territories, both of which would remain in the United Kingdom—a Northern Ireland and a Southern Ireland—that would both be quasi-autonomous, self-governing entities of the United Kingdom. But Irish nationalists had unilaterally declared an independent Ireland and launched a guerrilla campaign—the Irish War of Independence, or Anglo-Irish War (1919–21) and refused to recognize the act; they refused to reconcile themselves to remaining within the United Kingdom.

In December 1921, the British reconciled themselves to the nationalists’ demands and created an Irish Free State in the 26 counties of the south. Those counties were not yet an Irish Republic; they were a dominion within the British Empire, but no longer a part of the United Kingdom. The Irish Free State went its own way and in 1949 became the Republic of Ireland. So that was one critical respect in which partition did not go the way the British had meant it to.

WEAVER: They set themselves up for trouble right away with the way the border was drawn. The expectation at the time was that Northern Ireland would be left with the Protestant majority parts of Ulster, which only would have been four of the nine traditional counties. The thinking was that the area would simply be too small a state to be viable and that Northern Ireland would therefore eventually have to reconcile itself to inclusion within the Irish Free State. But the Irish Boundary Commission, established in the treaty ending the Anglo–Irish War, ultimately included six of the nine counties of Ulster within Northern Ireland, and that left a lot of nationalist areas like Tyrone, Fermanagh, and Omagh, all of which were Catholic-majority areas, stranded in Northern Ireland.

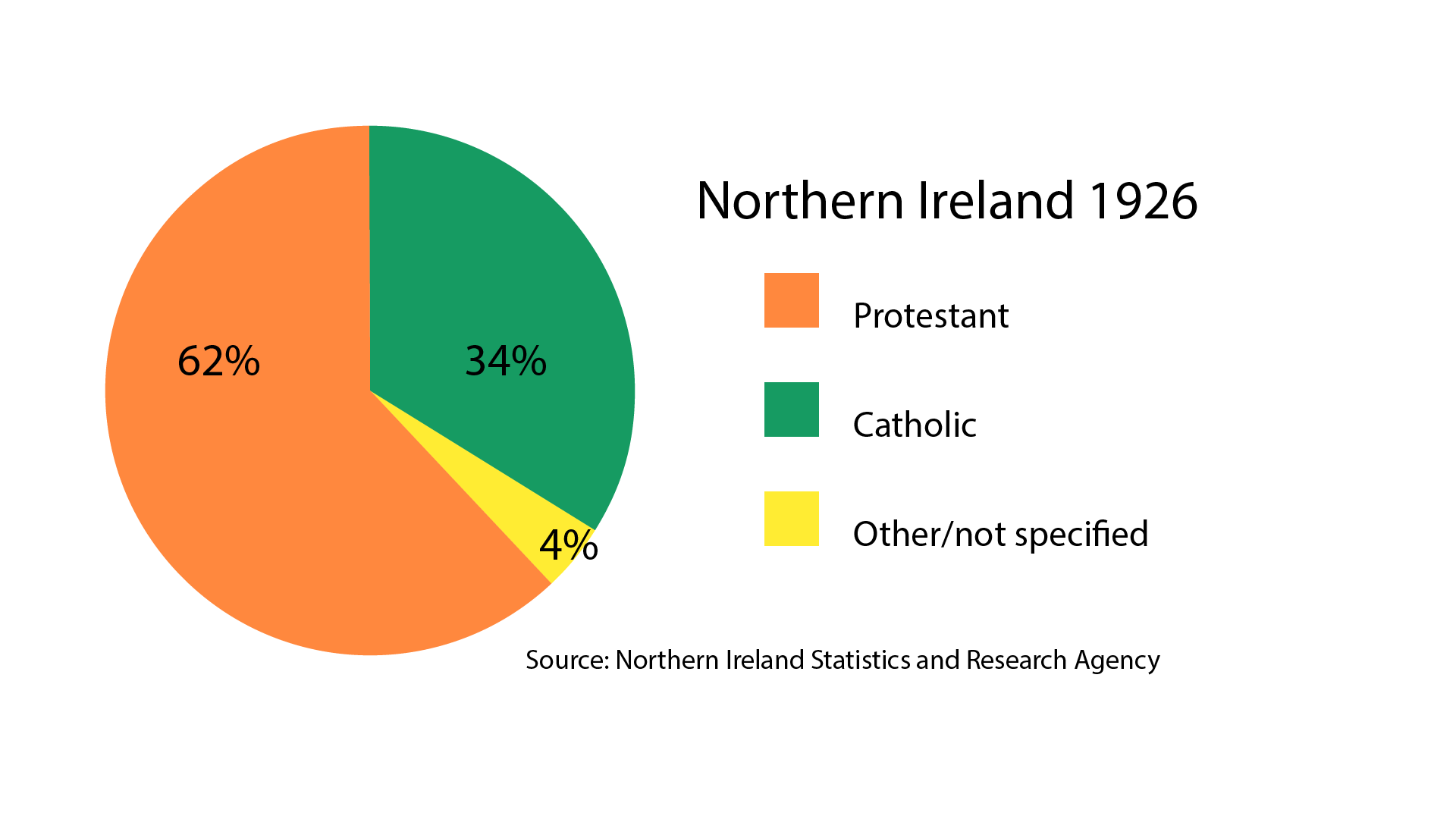

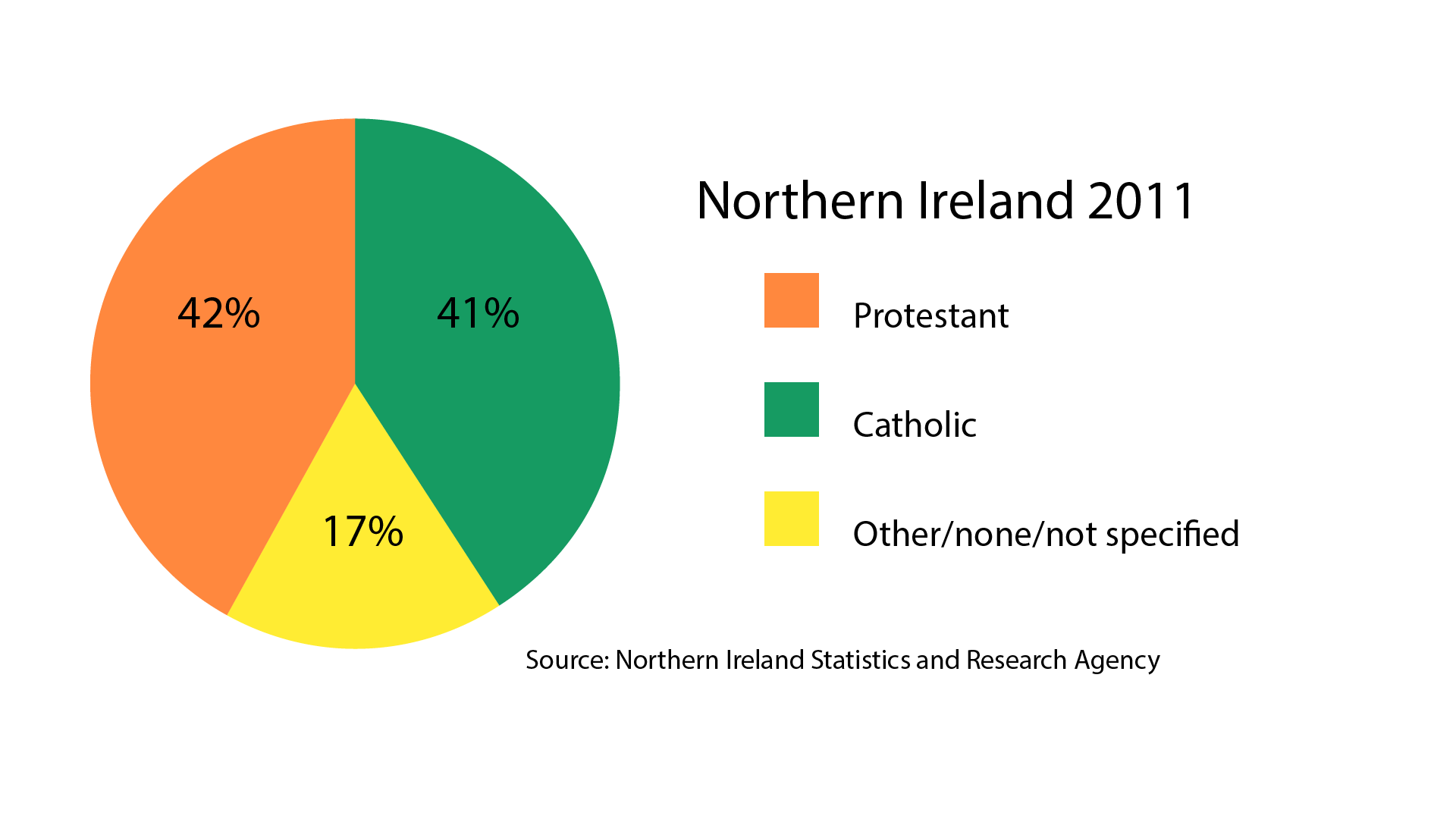

That fact made Northern Ireland a bigger entity than anyone had expected it to be and also heightened the animosities on both sides. It resulted in a resentful Catholic minority within Northern Ireland. Students often misunderstand this; they think of Northern Ireland as the Protestant-majority part of Ireland. And while it is the Protestant-majority part of Ireland, at the time of the division, about a third of the Northern Irish were Catholic.

Northern Ireland’s response to having an unreconciled, unhappy, large Catholic minority in their midst, was essentially to create a Protestant unionist one-party state, which governed with a heavy hand, to say the least. The Ulster Unionist Party in Northern Ireland wrote into law rampant discrimination against Catholics—in housing, employment, education, and job opportunities.

Meanwhile, the Irish Republic was also effectively a one-party state, strongly committed to cultural nationalism, with a lot of influence from the Roman Catholic Church, including a heavy infusion of doctrinaire Catholicism in the constitution. That was bound to heighten the resistance of Ulster Protestants to inclusion within anything like a united Ireland.

It was really a situation that was bound to explode at some point. And, indeed, when the civil rights movement in the 1960s came along, it did, with a 30-year period of violence, the Troubles.

WEAVER: Brexit takes Northern Ireland out of the European Union and leaves the Republic of Ireland in the European Union, drawing a stark distinction and difference between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It defies the whole spirit of the Good Friday Agreement, the power-sharing agreement that ended the Troubles, in 1998, and tended to diminish the distinctions between north and south.

Brexit has also activated a historic sense of betrayal on the part of the Northern Irish against Britain. One curious fact of the Northern Irish psyche that has been true for a long, long time, is that while they are intensely loyal to the crown and the union with Great Britain, there’s also no love lost between the Northern Irish unionists and Great Britain: the Irish unionists always feel let down, always feel betrayed. So there’s a fear that Brexit is going to strand Northern Ireland on the other side of a customs border in the Irish Sea. This is the main cause of the recent surge in unionist protest in Belfast.

Meanwhile, there’s also something calling itself the new IRA, a successor to the Irish Republican Army that emerged during the War of Independence. It’s now threatening to rise up to recommission weapons, to launch its own sort of campaign of retaliatory violence.

There’s been an unfortunate sort of heroic regard for the gunman-martyr throughout Irish history in the 20th century, certainly throughout the Northern Ireland conflict from the 1960s to the late 1990s: the rebel revolutionary who either dies, or is martyred at the hands of the state, or is executed. This cult exists on both sides of the confessional and political divide in Ireland. It’s a harmful romantic indulgence that both unionists and nationalists have been far too slow to condemn. We’ll see whether the latest scuffles between nationalists and unionists accelerate out of control, or whether this is just a temporary spasm, while Brexit sorts itself out.

WEAVER: Before Brexit, I would have said, “yes.” There was a kind of momentum and there seemed to be a will for reunification. The strong referendum in favor of the Good Friday Agreement on both sides of the border in Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, suggested that there was a political will, if not toward unification, at least toward reconciliation.

There are a lot of reasons that still make me think Ireland will eventually reunite. The demographics have changed. Protestants are no longer a clear majority in Northern Ireland. It’s more evenly split, with a growing percentage of people in the north of Ireland who do not align themselves either as Protestant or Catholic, which means there’s now a pretty sizable minority that is outside of this cultural antipathy altogether. And they don’t identify with Protestant unionists, nor with Catholic nationalists.

More importantly, from the 1980s onward, we see a liberalization in the Irish Republic, with a lessening hold of the Catholic Church on Irish culture, education, and the state. There has been a real move toward liberalization and secularization to align the Irish Republic with the rest of Europe, so they are no longer a kind of quasi-theocratic outlier, but instead a place that looks more like the rest of Europe, along with economic progress.

But then Brexit happened. Brexit, of course, doesn’t just present a challenge to the Irish and to the status of Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom. It is also deeply unpopular in Scotland, where it has renewed calls for a second referendum on independence. Ultimately, Brexit could implode the entire union of the United Kingdom. We’ll see.

On April 6, 1917, Congress voted to declare war on Germany, joining the bloody battle—then optimistically called the “Great War.” Rochester political scientist Hein Goemans explains why Germany was willing to risk American entry into the war.

In a new book, professor of history Stewart Weaver chronicles journeys of discovery from the pre-historic trek of humans across the Bering Strait to the mid-20th century deep sea voyages of Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

In a new book, historian Thomas Fleischman shows how the state’s approach to industrial pig farming foreshadowed its demise.