For women in the United States, health insurance has come a very long way in the last decade, thanks in large part to the dramatic improvements and consumer protections brought about by the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). This is particularly true in the individual/family market, where previous reforms and mandates had rarely applied.

Most of the law’s provisions were implemented at the beginning of 2014. Prior to that, more than half of individual plans charged higher premiums for a 40-year-old female non-smoker than for a 40-year-old male smoker. The practice of charging women more than men for the exact same coverage was costing women roughly $1 billion per year by 2012.

Despite the higher premiums paid by women, 90% of individual health plans didn’t provide any routine maternity benefits prior to the ACA.

And in all but five states, being pregnant was a pre-existing condition that prevented a woman from purchasing individual health insurance at all. (In most states, expectant fathers were also denied coverage, due to laws that require health insurance companies to automatically cover a member’s newborn child. To mitigate against the risk of having to cover a newborn with complications, most individual market insurers rejected applications from expectant parents, including both mothers and fathers.)

Many individual health plans offered no coverage for contraceptives, and coverage for women’s preventive care varied considerably from one state to another.

Prior to ACA implementation, some states had taken action to mitigate gender inequality in health insurance. By 2012, 14 states had banned or restricted gender-based premiums in the individual market, 17 had done so for the group market, and nine states had laws requiring maternity coverage in the individual market. But in most states, gender discrimination was still the norm until 2014.

Obamacare’s first major improvement for women took effect in August 2012. For plan years beginning on or after August 1, 2012, all non-grandfathered policies were required to provide coverage for eight women-specific categories of preventive care. And this was in addition to the broad range of preventive services for both men and women that were added with no cost-sharing to all non-grandfathered plans in September 2010.

But things got significantly better in January 2014 when all new policies had to be fully ACA-compliant. Maternity coverage is now included on all new major medical plans. Most employer-sponsored health plans already covered maternity care, under the Pregnancy Discrimination Act that had been enacted in 1978. But the nationwide requirement for maternity coverage on individual/family health plans was due entirely to the ACA. Also as a result of the ACA, premiums can no longer be based on gender. (Only age, geographic location, and tobacco use can be factored into premiums.)

Pre-existing conditions are no longer used to determine premiums or eligibility for coverage, which means that pregnant women (and expectant fathers) can obtain health insurance in the individual market in every state — assuming they are applying during open enrollment or have a qualifying event that allows them to enroll. (In some states, pregnancy itself is a qualifying event that triggers a special enrollment period. But that is not the case in most states.)

Obamacare has been a boon for women’s health. But although things are far better than they were just a few years ago, there have been some legal challenges that eroded some of the newfound access to contraceptive coverage. This continues to be an evolving topic as of 2023.

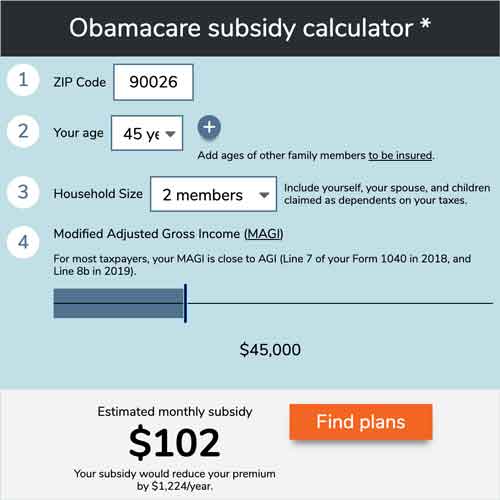

Use our calculator to estimate how much you could save on your ACA-compliant health insurance premiums.

The women’s preventive care mandate that went into effect in 2012 requires health insurance policies to cover “All Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient education and counseling for all women with reproductive capacity.” (Note that the ACA does not specify which preventive services would have to be covered in full; it was left to HHS to sort out the details, so the contraceptive mandate stems from ACA implementation regulations, rather than the text of the ACA itself.)

But in 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that Hobby Lobby and other closely held corporations do not have to provide coverage for the FDA-approved contraceptives that Hobby Lobby deems abortifacients (emergency contraceptives, including Ella and Plan B, and intrauterine devices or IUDs).

In the majority’s opinion on the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby case, Justice Alito frequently mentioned the Obama Administration’s accommodation that already allowed churches and religious employers to opt out of directly paying for contraceptive coverage, while still providing female employees with access to contraceptives. Full details are in this Federal Register Notice. In summary, the insurer – or in the case of self-insured plans, the third-party administrator – provides contraceptive coverage to employees with no cost-sharing, and with no premiums or fees charged to the religious employer for that portion of the coverage. Thus the financial responsibility for providing contraceptive coverage falls to the insurer or administrator rather than the religious organization that sponsors the health insurance plan.

With the exception of IUDs, Ella, and Plan B, Hobby Lobby continued to cover all FDA-approved contraceptives for women. But there were also lawsuits arguing that the ACA’s entire contraceptive mandate should not apply to religious employers or for-profit employers that object on religious or moral grounds. And the Trump administration finalized guidance in 2017 that broadened the exemptions to include religious or moral exceptions, and made the Obama administration accommodation process optional for employers that object to the contraception coverage mandate.

A challenge to the Trump administration’s rules reached the Supreme Court, and the Court ultimately upheld the Trump administration’s rule, allowing employers broad access to religious or moral exceptions to the contraceptive mandate.

But in 2023, the Biden administration proposed a new rule change that would walk back the provisions that the Trump administration had put in place. Specifically, it would remove the ability for employers and plan issuers to use a moral objection in order to be exempt from the contraception coverage mandate (only sincerely held religious objections would be allowed). And it would also create an “independent pathway” through which women would be able to obtain zero-cost contraception even if they’re enrolled in a health plan that has an exemption from the contraceptive coverage mandate and has not utilized the existing accommodation process (which was made optional by the Trump administration). The proposed rule can be seen here, and public comments on it are being accepted by HHS in early 2023.

Yes, the use of long-acting reversible contraception (IUDs and implants) increased significantly once the ACA’s zero-cost coverage rules took effect. IUDs are among the most effective contraceptives, and are not subject to user error, which is often a factor in contraceptive failure. However, their initial cost (usually $500 to $1,000) is a significant deterrent if women have to pay for them out-of-pocket.

But long-term, they are more cost-effective than most other contraceptive methods. And when the up-front cost barrier is removed – as it is under the ACA – women are much more likely to select long-term birth control. And as access to birth control, especially long-acting birth control, has improved due to the ACA, the abortion rate has fallen.

Colorado’s teen birth rate and abortion rate both dropped significantly from 2009 through 2017, mainly because of a grant that provided free or low-cost IUDs to young women who would otherwise not be able to afford them. The Colorado program was funded by an anonymous donor, prior to the ACA’s reforms. But for women who have health insurance, anonymous donors are no longer necessary.

Nearly all women with health insurance – private coverage and Medicaid – have access to highly effective, long-term contraceptives now, without a cost barrier (as noted above, the Biden administration has proposed a rule change to ensure that women whose plan issuers are exempt from providing contraceptive coverage would still have a means of accessing zero-cost contraception). The ACA’s coverage mandate has translated to an increase in the number of women relying on these methods of birth control (especially among women enrolled in health plans with high deductibles), and a sharp reduction in out-of-pocket spending on contraception in general.

We must not forget about the hundreds of thousands of American women who are currently in the coverage gap in states that have not expanded Medicaid. The ACA provided Medicaid for people with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level (with exchange subsidies picking up where Medicaid ends), but the Supreme Court ruled that states could opt out of Medicaid expansion, and there are still 12 states — mostly in the southeastern US — that have not expanded Medicaid.

Women in those states are not eligible for subsidies to purchase exchange plans unless their incomes are at least 100% of the poverty level. But the stringent guidelines for Medicaid eligibility in 11 of those 12 states (all but Wisconsin) mean that many women with incomes below the exchange subsidy threshold are not eligible for Medicaid either – they earn too much for Medicaid but too little for exchange subsidies.

The ACA’s health insurance reforms remain unavailable to women for whom health insurance itself is out of reach.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.