Ordinarily only the parties to a contract have the right to enforce that contract. To this point in our studies, we have focused on the rights and duties of the two parties to a contract. The laws surrounding third-party rights govern the ability of third parties or outsiders to enforce contractual rights or to be bound by contractual obligations even though they are not a party to a contract. This allows individuals or entities that are not directly involved in a contract to benefit from or be bound by the contract’s terms.

There are several reasons why third-party rights in contracts exists. One reason is to ensure fairness and equity in contractual relationships. In many cases, outsiders may have a legitimate interest in the performance of a contract, and allowing them to enforce their rights or obligations under the contract can prevent injustice and promote the overall fairness of the legal system. Another is to promote efficiency and convenience in contractual relationships. By allowing outsiders to enforce their rights or obligations under a contract, parties to a contract can avoid the need for multiple contracts or legal actions, which can save time and resources. Finally, third-party rights can be used to facilitate economic transactions. In many industries, such as construction and real estate, contracts often involve multiple parties with different interests and responsibilities. Allowing outsiders to enforce rights or obligations under a contract can help ensure that everyone involved in a transaction is held accountable and that the transaction proceeds smoothly. This Chapter explores contracts where outsiders acquire rights or duties or both by considering:

Assignees (outsiders who acquire rights after the contract is made)

Delegatees (outsiders who acquire duties after the contract is made)

Third-party beneficiaries (outsiders who acquire rights when the original contract is made)

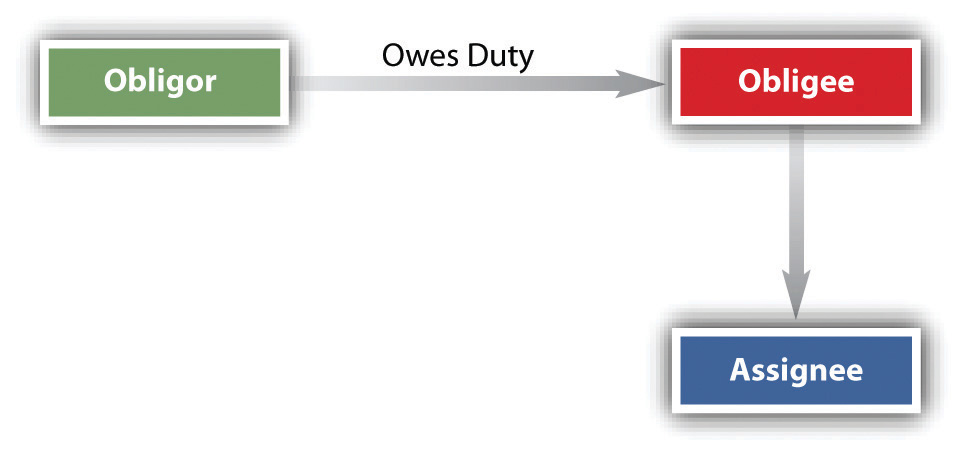

Contracts create rights and obligations between contracting parties. An assignment is the transfer of rights under a contract from one party (the assignor) to another party (the assignee). When a party assigns their rights under a contract, they are essentially transferring their ability to receive benefits or enforce terms of the contract to someone else. Stated another way, an assignment occurs when an obligee (one who has the right to receive a contract benefit) transfers a right to receive a contract benefit owed by the obligor (the one who has a duty to perform) to a third person ( assignee ); the obligee then becomes an assignor (one who makes an assignment). So, the party that makes the assignment is both an obligee and an assignor. The assignee acquires the right to receive the contractual obligations of the promisor, who is referred to as the obligor.

Generally, the assignor may assign any right unless (1) doing so would materially change the obligation of the obligor, materially burden him, increase his risk, or otherwise diminish the value to him of the original contract; (2) statute or public policy forbids the assignment; or (3) the contract itself precludes assignment. The common law of contracts and Articles 2 and 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) govern assignments. Assignments are a common occurrence in business, legal, and financial transactions.

To effect an assignment, the assignor must make known his intention to transfer the rights to the third person. This intention must take place in the present – it cannot be a future intention. The assignor’s intention must be that the assignment is effective without need of any further action or any further manifestation of intention to make the assignment. Under the UCC, any assignments of rights in excess of $5,000 must be in writing, but otherwise, assignments can be oral and consideration is not required: the assignor could assign the right to the assignee for no exchange of money or any other consideration. For example, Mrs. Franklin has the right to receive $750 a month from the sale of a house she formerly owned; she assigns the right to receive the money to her son Jason, as a gift. The assignment is good, and need not be written.

For the assignment to become effective, the assignee must manifest his acceptance under most circumstances. This is done automatically when, as is usually the case, the assignee has given consideration for the assignment (i.e., there is a contract between the assignor and the assignee in which the assignment is the assignor’s consideration), and then the assignment is not revocable without the assignee’s consent. Problems of acceptance normally arise only when the assignor intends the assignment as a gift. Then, for the assignment to be irrevocable, either the assignee must manifest his acceptance or the assignor must notify the assignee in writing of the assignment. Thus, if Mrs. Franklin assigns the $750 a month from the sale of her house to her son Jason as a gift, this assignment is valid, but revocable.

Notice to the obligor is not required, but an obligor who renders performance to the assignor without notice of the assignment (that performance of the contract is to be rendered now to the assignee) is discharged from their obligation within the contract. Obviously, the assignor cannot then keep the consideration he has received; he owes it to the assignee. But if notice is given to the obligor and she performs to the assignor anyway, the assignee can recover from either the obligor or the assignee, so the obligor could have to perform twice. Of course, an obligor who receives notice of the assignment from the assignee will want to be sure the assignment has really occurred. After all, anybody could waltz up to the obligor and say, “I’m the assignee of your contract with the bank. From now on, pay me the $500 a month, not the bank.” The obligor is entitled to verification of the assignment.

An assignment of rights effectively makes the assignee stand in the shoes of the assignor. He gains all the rights against the obligor that the assignor had, but no more. An obligor who could avoid the assignor’s attempt to enforce the rights could avoid a similar attempt by the assignee. Suppose Dealer sells a car to Buyer on a contract where Buyer is to pay $300 per month and the car is warranted for 50,000 miles. If the car goes on the fritz before then and Dealer won’t fix it, Buyer could fix it for, say, $250 and deduct that $250 from the amount owed Dealer on the next installment. Now, if Dealer assigns the contract to Assignee, Assignee stands in Dealer’s shoes, and Buyer could likewise deduct the $250 from payment to Assignee.

The “shoe rule” does not apply to two types of assignments. First, it is inapplicable to the sale of a negotiable instrument to a holder in due course. Second, the rule may be waived: under the UCC and at common law, the obligor may agree in the original contract not to raise defenses against the assignee that could have been raised against the assignor. While a waiver of defenses makes the assignment more marketable from the assignee’s point of view, it is a situation fraught with peril to an obligor, who may sign a contract without understanding the full import of the waiver. Under the waiver rule, for example, a farmer who buys a tractor on credit and discovers later that it does not work would still be required to pay a credit company that purchased the contract; his defense that the merchandise was shoddy would be unavailing (he would, as used to be said, be “having to pay on a dead horse”).

For that reason, there are various rules that limit both the holder in due course and the waiver rule. Certain defenses, the so-called real defenses (infancy, duress, and fraud in the execution, among others), may always be asserted. Also, the waiver clause in the contract must have been presented in good faith, and if the assignee has actual notice of a defense that the buyer or lessee could raise, then the waiver is ineffective. Moreover, in consumer transactions, the UCC’s rule is subject to state laws that protect consumers (people buying things used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes), and many states, by statute or court decision, have made waivers of defenses ineffective in such consumer transactions . Federal Trade Commission regulations also affect the ability of many sellers to pass on rights to assignees free of defenses that buyers could raise against them. Because of these various limitations on the holder in due course and on waivers, the “shoe rule” will not govern in consumer transactions and, if there are real defenses or the assignee does not act in good faith, in business transactions as well.

The general rule—as previously noted—is that most contract rights are assignable, and the law favors freely assignable rights. There are five exceptions to this rule however.

When an assignment has the effect of materially changing the duties that the obligor must perform, it is ineffective. Changing the party to whom the obligor must make a payment is not a material change of duty that will defeat an assignment, since that, of course, is the purpose behind most assignments. Nor will a minor change in the duties the obligor must perform defeat the assignment. But, some changes are significant enough to bar assignments.

Several residents in the town of Centerville sign up on an annual basis with the Centerville Times to receive their morning paper. A customer who is moving out of town may assign his right to receive the paper to someone else within the delivery route. As long as the assignee pays for the paper, the assignment is effective; the only relationship the obligor has to the assignee is a routine delivery in exchange for payment. But if the change involves assigning the right to receive the paper to someone that is outside of the delivery route, that change would be material, and the assignment could be invalid.

When it matters to the obligor who receives the benefit of his duty to perform under the contract, then the receipt of the benefit is a personal right that cannot be assigned. For example, a student seeking to earn pocket money during the school year signs up to do research work for a professor she admires and with whom she is friendly. The professor assigns the contract to one of his colleagues with whom the student does not get along. The assignment is ineffective because it matters to the student (the obligor) who the person of the assignee is. It is for this same reason that tenants usually cannot assign (sublet) their tenancies without the landlord’s permission because it matters to the landlord who the person is that is living in the landlord’s property.

Nassau Hotel Co. v. Barnett & Barse Corporation, 147 N.Y.S. 283 (1914)

Plaintiff owns a hotel at Long Beach, L. I., and on the 21st of November, 1912, it entered into a written agreement with the individual defendants Barnett and Barse to conduct the same for a period of years.…Shortly after this agreement was signed, Barnett and Barse organized the Barnett & Barse Corporation with a capital stock of $10,000, and then assigned the agreement to it. Immediately following the assignment, the corporation went into possession and assumed to carry out its terms. The plaintiff thereupon brought this action to cancel the agreement and to recover possession of the hotel and furniture therein, on the ground that the agreement was not assignable. [Summary judgment in favor of the plaintiff, defendant corporation appeals.]

The only question presented is whether the agreement was assignable. It provided, according to the allegations of the complaint, that the plaintiff leased the property to Barnett and Barse with all its equipment and furniture for a period of three years, with a privilege of five successive renewals of three years each. It expressly provided:

‘That said lessees…become responsible for the operation of the said hotel and for the upkeep and maintenance thereof and of all its furniture and equipment in accordance with the terms of this agreement and the said lessees shall have the exclusive possession, control and management thereof. * * * The said lessees hereby covenant and agree that they will operate the said hotel at all times in a first-class business-like manner, keep the same open for at least six (6) months of each year, * * *’ and ‘in lieu of rental the lessor and lessees hereby covenant and agree that the gross receipts of such operation shall be, as received, divided between the parties hereto as follows: (a) Nineteen per cent. (19%) to the lessor. * * * In the event of the failure of the lessees well and truly to perform the covenants and agreements herein contained,’ they should be liable in the sum of $50,000 as liquidated damages. That ‘in consideration and upon condition that the said lessees shall well and faithfully perform all the covenants and agreements by them to be performed without evasion or delay the said lessor for itself and its successors, covenants and agrees that the said lessees, their legal representatives and assigns may at all times during said term and the renewals thereof peaceably have and enjoy the said demised premises.’ And that ‘this agreement shall inure to the benefit of and bind the respective parties hereto, their personal representatives, successors and assigns.’

The complaint further alleges that the agreement was entered into by plaintiff in reliance upon the financial responsibility of Barnett and Barse, their personal character, and especially the experience of Barnett in conducting hotels; that, though he at first held a controlling interest in the Barnett & Barse Corporation, he has since sold all his stock to the defendant Barse, and has no interest in the corporation and no longer devotes any time or attention to the management or operation of the hotel.

…[C]learly…the agreement in question was personal to Barnett and Barse and could not be assigned by them without the plaintiff’s consent. By its terms the plaintiff not only entrusted them with the care and management of the hotel and its furnishings—valued, according to the allegations of the complaint, at more than $1,000,000—but agreed to accept as rental or compensation a percentage of the gross receipts. Obviously, the receipts depended to a large extent upon the management, and the care of the property upon the personal character and responsibility of the persons in possession. When the whole agreement is read, it is apparent that the plaintiff relied, in making it, upon the personal covenants of Barnett and Barse. They were financially responsible. As already said, Barnett had had a long and successful experience in managing hotels, which was undoubtedly an inducing cause for plaintiff’s making the agreement in question and for personally obligating them to carry out its terms.

It is suggested that because there is a clause in the agreement to the effect that it should ‘inure to the benefit of and bind the respective parties hereto, their personal representatives and assigns,’ that Barnett and Barse had a right to assign it to the corporation. But the intention of the parties is to be gathered, not from one clause, but from the entire instrument [Citation] and when it is thus read it clearly appears that Barnett and Barse were to personally carry out the terms of the agreement and did not have a right to assign it. This follows from the language used, which shows that a personal trust or confidence was reposed by the plaintiff in Barnett and Barse when the agreement was made.

In [Citation] it was said: “Rights arising out of contract cannot be transferred if they…involve a relation of personal confidence such that the party whose agreement conferred those rights must have intended them to be exercised only by him in whom he actually confided.”

This rule was applied in [Citation] the court holding that the plaintiff—the assignee—was not only technically, but substantially, a different entity from its predecessor, and that the defendant was not obliged to entrust its money collected on the sale of the presses to the responsibility of an entirely different corporation from that with which it had contracted, and that the contract could not be assigned to the plaintiff without the assent of the other party to it.

The reason which underlies the basis of the rule is that a party has the right to the benefit contemplated from the character, credit, and substance of him with whom he contracts, and in such case he is not bound to recognize…an assignment of the contract.

The order appealed from, therefore, is affirmed.

Case questions

Various federal and state laws prohibit or regulate some contract assignments. For example, the assignment of future wages is regulated by state and federal law, such an attempt to try to effect such an assignment would not be valid. And even in the absence of statute, public policy might prohibit some assignments.

A written contract may contain general language that prohibits assignment of rights or assignment of “the contract.” Both the Restatement and UCC Section 2-210(3) declare that in the absence of any contrary circumstances, a provision in the agreement that prohibits assigning “the contract” bars “only the delegation to the assignee of the assignor’s performance.” In other words, unless the contract specifically prohibits assignment of any of its terms, a party is free to assign anything except his or her own duties. Even if a contractual provision explicitly prohibits it, a right to damages for breach of the whole contract is assignable under UCC Section 2-210(2) in contracts for goods. Likewise, UCC Section 9-318(4) invalidates any contract provision that prohibits assigning sums already due or to become due. Indeed, in some states, at common law, a clause specifically prohibiting assignment will fail. For example, the buyer and the seller agree to the sale of land and to a provision barring assignment of the rights under the contract. The buyer pays the full price, but the seller refuses to convey. The buyer then assigns to her friend the right to obtain title to the land from the seller. The latter’s objection that the contract precludes such an assignment will fall on deaf ears in some states; the assignment is effective, and the friend may sue for the title. Bottom line, even though a contract may expressly state it cannot be assigned, that may not always be the case.

Rose v. Vulcan Materials Co. 194 S.E.2d 521 (N.C. 1973)

…Plaintiff [Rose], after leasing his quarry to J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc., promised not to engage in the rock-crushing business within an eight-mile radius of [the city of] Elkin for a period of ten years. In return for this promise, J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc., promised, among other things, to furnish plaintiff stone f.o.b. the quarry site at Cycle, North Carolina, at stipulated prices for ten years.…

By a contract effective 23 April 1960, Vulcan Materials Company, a corporation…, purchased the stone quarry operations and the assets and obligations of J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc.…[Vulcan sent Rose a letter, part of which read:]

Mr. Dooley brought to us this morning the contracts between you and his companies, copies of which are attached. This is to advise that Vulcan Materials Company assumes all phases of these contracts and intends to carry out the conditions of these contracts as they are stated.

In early 1961 Vulcan notified plaintiff that it would no longer sell stone to him at the prices set out in [the agreement between Rose and Dooley] and would thereafter charge plaintiff the same prices charged all of its other customers for stone. Commencing 11 May 1961, Vulcan raised stone prices to the plaintiff to a level in excess of the prices specified in [the Rose-Dooley agreement].

At the time Vulcan increased the prices of stone to amounts in excess of those specified in [the Rose-Dooley contract], plaintiff was engaged in his ready-mix cement business, using large quantities of stone, and had no other practical source of supply. Advising Vulcan that he intended to sue for breach of contract, he continued to purchase stone from Vulcan under protest.…

The total of these amounts over and above the prices specified in [the Rose-Dooley contract] is $25,231.57, [about $260,000 in 2024 dollars] and plaintiff seeks to recover said amount in this action.

The [Rose-Dooley] agreement was an executory bilateral contract under which plaintiff’s promise not to compete for ten years gained him a ten-year option to buy stone at specified prices. In most states, the assignee of an executory bilateral contract is not liable to anyone for the nonperformance of the assignor’s duties thereunder unless he expressly promises his assignor or the other contracting party to perform, or ‘assume,’ such duties.…These states refuse to imply a promise to perform the duties, but if the assignee expressly promises his assignor to perform, he is liable to the other contracting party on a third-party beneficiary theory. And, if the assignee makes such a promise directly to the other contracting party upon a consideration, of course he is liable to him thereon. [Citation]

A minority of states holds that the assignee of an executory bilateral contract under a general assignment becomes not only assignee of the rights of the assignor but also delegatee of his duties; and that, absent a showing of contrary intent, the assignee impliedly promises the assignor that he will perform the duties so delegated. This rule is expressed in Restatement, Contracts, s 164 (1932) as follows:

(1) Where a party under a bilateral contract which is at the time wholly or partially executory on both sides purports to assign the whole contract, his action is interpreted, in the absence of circumstances showing a contrary intention, as an assignment of the assignor’s rights under the contract and a delegation of the performance of the assignor’s duties.

(2) Acceptance by the assignee of such an assignment is interpreted, in the absence of circumstances showing a contrary intention, as both an assent to become an assignee of the assignor’s rights and as a promise to the assignor to assume the performance of the assignor’s duties.’ (emphasis added)

We…adopt the Restatement rule and expressly hold that the assignee under a general assignment of an executory bilateral contract, in the absence of circumstances showing a contrary intention, becomes the delegatee of his assignor’s duties and impliedly promises his assignor that he will perform such duties.

The rule we adopt and reaffirm here is regarded as the more reasonable view by legal scholars and textwriters. Professor Grismore says:

It is submitted that the acceptance of an assignment in this form does presumptively import a tacit promise on the part of the assignee to assume the burdens of the contract, and that this presumption should prevail in the absence of the clear showing of a contrary intention. The presumption seems reasonable in view of the evident expectation of the parties. The assignment on its face indicates an intent to do more than simply to transfer the benefits assured by the contract. It purports to transfer the contract as a whole, and since the contract is made up of both benefits and burdens both must be intended to be included.…Grismore, Is the Assignee of a Contract Liable for the Nonperformance of Delegated Duties? 18 Mich.L.Rev. 284 (1920).

In addition, with respect to transactions governed by the Uniform Commercial Code, an assignment of a contract in general terms is a delegation of performance of the duties of the assignor, and its acceptance by the assignee constitutes a promise by him to perform those duties. Our holding in this case maintains a desirable uniformity in the field of contract liability.

We further hold that the other party to the original contract may sue the assignee as a third-party beneficiary of his promise of performance which he impliedly makes to his assignor, under the rule above laid down, by accepting the general assignment. Younce v. Lumber Co., [Citation] (1908), holds that where the assignee makes an express promise of performance to his assignor, the other contracting party may sue him for breach thereof. We see no reason why the same result should not obtain where the assignee breaches his promise of performance implied under the rule of Restatement s 164. ‘That the assignee is liable at the suit of the third party where he expressly assumes and promises to perform delegated duties has already been decided in a few cases (citing Younce). If an express promise will support such an action it is difficult to see why a tacit promise should not have the same effect.’ Grismore, supra. Parenthetically, we note that such is the rule under the Uniform Commercial Code, [2-210].

We now apply the foregoing principles to the case at hand. The contract of 23 April 1960, between defendant and J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc., under which, as stipulated by the parties, ‘the defendant purchased the assets and obligations of J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc.,’ was a general assignment of all the assets and obligations of J. E. Dooley and Son, Inc., including those under [the Rose-Dooley contract]. When defendant accepted such assignment it thereby became delegatee of its assignor’s duties under it and impliedly promised to perform such duties.

When defendant later failed to perform such duties by refusing to continue sales of stone to plaintiff at the prices specified in [the Rose-Dooley contract], it breached its implied promise of performance and plaintiff was entitled to bring suit thereon as a third-party beneficiary.

The decision…is reversed with directions that the case be certified to the Superior Court of Forsyth County for reinstatement of the judgment of the trial court in accordance with this opinion.

Case questions

The law distinguishes between assigning future rights under an existing contract and assigning rights that will arise from a future contract. Rights contingent on a future event can be assigned in exactly the same manner as existing rights, as long as the contingent rights are already incorporated in a contract. Ben has a long-standing deal with his neighbor, Mrs. Robinson, to keep the latter’s walk clear of snow at twenty dollars a snowfall. Ben is saving his money for a new printer, but when he is eighty dollars shy of the purchase price, he becomes impatient and cajoles a friend into loaning him the balance. In return, Ben assigns his friend the earnings from the next four snowfalls. The assignment is effective. However, a right that will arise from a future contract cannot be the subject of a present assignment.

An assignor may assign part of a contractual right, but only if the obligor can perform that part of his contractual obligation separately from the remainder of his obligation. Assignment of part of a payment due is always enforceable. However, if the obligor objects, neither the assignor nor the assignee may sue him unless both are party to the suit. Mrs. Robinson owes Ben one hundred dollars. Ben assigns fifty dollars of that sum to his friend. Mrs. Robinson is perplexed by this assignment and refuses to pay until the situation is explained to her satisfaction. The friend brings suit against Mrs. Robinson. The court cannot hear the case unless Ben is also a party to the suit. This ensures all parties to the dispute are present at once and avoids multiple lawsuits.

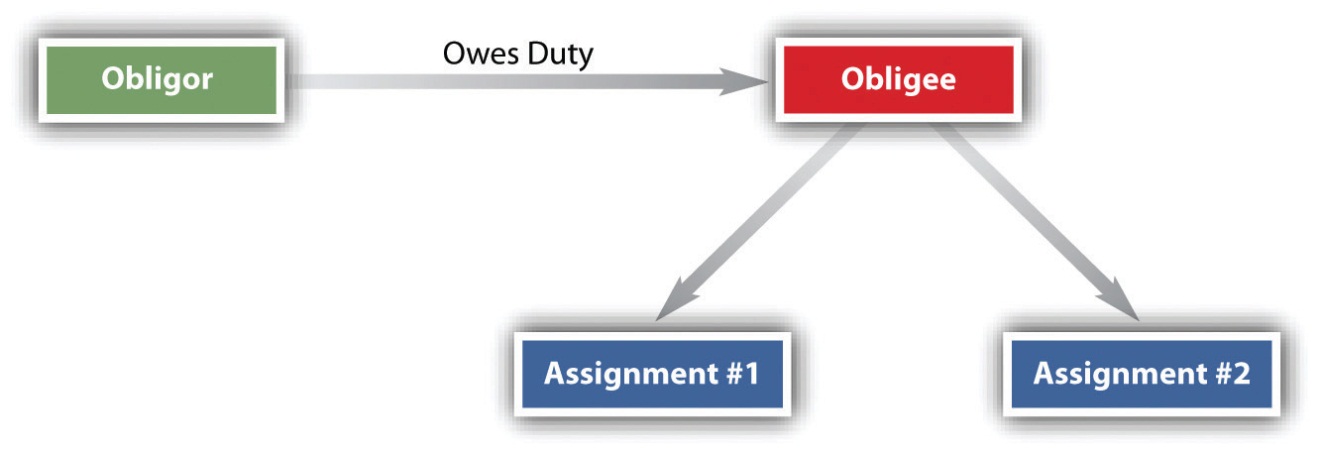

It may happen that an assignor assigns the same interest twice. With certain exceptions, the first assignee takes precedence over any subsequent assignee. One obvious exception is when the first assignment is ineffective or revocable. A subsequent assignment has the effect of revoking a prior assignment that is ineffective or revocable. Another exception: if in good faith the subsequent assignee gives consideration for the assignment and has no knowledge of the prior assignment, he takes precedence whenever he obtains payment from, performance from, or a judgment against the obligor, or whenever he receives some tangible evidence from the assignor that the right has been assigned (e.g., a bank deposit book or an insurance policy).

Some states follow the different English rule: the first assignee to give notice to the obligor has priority, regardless of the order in which the assignments were made. Furthermore, if the assignment falls within the filing requirements of UCC Article 9 the first assignee to file will prevail.

An assignor has legal responsibilities in making assignments. Unless the contract explicitly states to the contrary, a person who assigns a right for value makes certain assignor’s warranties to the assignee: that he will not upset the assignment, that he has the right to make it, and that there are no defenses that will defeat it. However, the assignor does not guarantee payment; assignment does not by itself amount to a warranty that the obligor is solvent or will perform as agreed in the original contract. Mrs. Robinson owes Ben fifty dollars. Ben assigns this sum to his friend. Before the friend collects, Ben releases Mrs. Robinson from her obligation. The friend may sue Ben for the fifty dollars. Or again, if Ben represents to his friend that Mrs. Robinson owes him (Ben) fifty dollars and assigns his friend that amount, but in fact Mrs. Robinson does not owe Ben that much, then Ben has breached his assignor’s warranty. The assignor’s warranties may be express or implied.

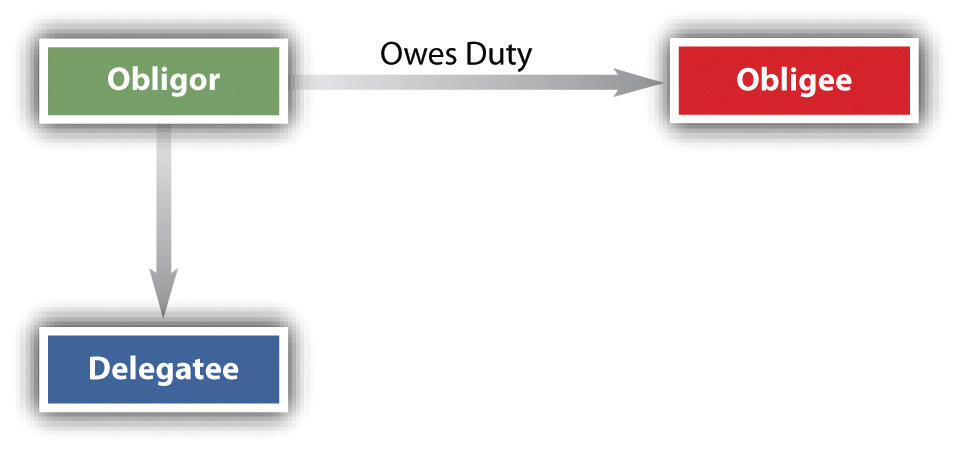

To this point, we have been considering the assignment of the assignor’s rights (usually, though not solely, to money payments). But in every contract, a right connotes a corresponding duty, and these may be delegated. A delegation is the transfer to a third party of the duty to perform under a contract. The one who delegates is the delegator . Because most obligees are also obligors, most assignments of rights will simultaneously carry with them the delegation of duties. Unless public policy or the contract itself bars the delegation, it is legally enforceable.

In most states, at common law, duties must be expressly delegated. Under Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) Section 2-210(4) and in a minority of states at common law an assignment of “the contract” or of “all my rights under the contract” is not only an assignment of rights but also a delegation of duties to be performed; by accepting the assignment, the delegatee (one to whom the delegation is made) implies a promise to perform the duties.

An obligor who delegates a duty (and becomes a delegator) does not thereby escape liability for performing the duty himself. The obligee of the duty may continue to look to the obligor for performance unless the original contract specifically provides for substitution by delegation. This is a big difference between assignment of contract rights and delegation of contract duties: in the former, the assignor is discharged (absent breach of assignor’s warranties); in the latter, the delegator remains liable. The obligee (again, the one to whom the duty to perform flows) may also, in many cases, look to the delegatee, because the obligee becomes an intended beneficiary of the contract between the obligor and the delegatee, as discussed in. Of course, the obligee may subsequently agree to accept the delegatee and discharge the obligor from any further responsibility for performing the duty. A contract among three persons having this effect is called a novation ; it is a new contract. Fred sells his house to Lisa, who assumes his mortgage. Fred, in other words, has delegated the duty to pay the bank to Lisa. If Lisa defaults, Fred continues to be liable to the bank, unless in the original mortgage agreement a provision specifically permitted any purchaser to be substituted without recourse to Fred, or unless the bank subsequently accepts Lisa and discharges Fred.

Many duties may be delegated. Indeed, if they could not be delegated, much of the world’s work would not get done. If you hire a construction company and an architect to design and build your house to certain specifications, the contractor may in turn hire individual craftspeople—plumbers, electricians, and the like—to do these specialized jobs, and as long as they are performed to specification, the contract terms will have been met. If you hired an architecture firm, though, you might not be contracting for the specific services of a particular individual in that firm. Yet, as was the case with assignments, there are certain duties that cannot be delegated. These are discussed below.

Personal services are not delegable. If a contract is such that the promisee expects the obligor personally to perform the duty, the obligor may not delegate it. Suppose the Catskill Civic Opera Association hires a famous singer to sing in its production of Carmen and the singer delegates the job to her understudy. The delegation is ineffective, and performance by the understudy does not absolve the famous singer of liability for breach.

Public policy may prohibit certain kinds of delegations. A public official, for example, may not delegate the duties of her office to private citizens, although various statutes generally permit the delegation of duties to her assistants and subordinates.

As we have already noted, the contract itself may bar assignment. The law generally disfavors restricting the right to assign a benefit, but it will uphold a contract provision that prohibits delegation of a duty. Thus, as we have seen, UCC Section 2-210(3) states that in a contract for sale of goods, a provision against assigning “the contract” is to be construed only as a prohibition against delegating the duties.

With assignments and delegations, we observed situations in which third-parties were brought into a pre-existing contract. An intended third-party beneficiary, on the other hand, is a party that was considered at the time the contract was made, and is part of the purpose for the contract in the first place. A party to a contract cannot enforce its terms; b ut if the party is intended to benefit from the performance of a contract between others, it makes sense that they should be able to enforce the contract.

In the vocabulary of the Restatement, a third person whom the parties to the contract intend to benefit is an intended beneficiary —that is, one who is entitled under the law of contracts to assert a right arising from a contract to which he or she is not a party. There are two types of intended beneficiaries.

A creditor beneficiary is one to whom the promisor agrees to pay a debt of the promisee . For example, a father is bound by law to support his child. If the child’s uncle (the promisor) contracts with the father (the promisee ) to furnish support for the child, the child is a creditor beneficiary and could sue the uncle. Or again, suppose Customer pays Ace Dealer for a new car, and Ace delegates the duty of delivery to Beta Dealer. Ace is now a debtor: he owes Customer something: a car. Customer is a creditor; she is owed something: a car. When Beta performs under his delegated contract with Ace, Beta is discharging the debt Ace owes to Customer. Customer is a creditor beneficiary of Dealers’ contract and could sue either one for nondelivery . She could sue Ace because she made a contract with him, and she could sue Beta because—again—she was intended to benefit from the performance of Dealers’ agreement.

The second type of intended beneficiary is a donee beneficiary . When the promisee is not indebted to the third person but intends for him or her to have the benefit of the promisor’s performance, the third person is a donee beneficiary (and the promise is sometimes called a gift promise). For example, an insurance company (the promisor) promises to its policyholder (the promisee ), in return for a premium, to pay $100,000 to his wife on his death; this makes the wife a donee beneficiary. The wife could sue to enforce the contract although she was not a party to it.

If a person is not an intended beneficiary—not a creditor or donee beneficiary—then he or she is said to be only an incidental beneficiary , and that person has no rights. An incidental third-party beneficiary is a party who may actually benefit from a contract between two other parties, but that benefit is like a side effect of the contract, because the contract itself was not specifically intended to benefit them. In other words, the third party is not a direct party to the contract but might still receive some benefits from the contract if it is performed as intended. Incidental beneficiaries have no legal right to enforce the contract or sue for damages if the contract is breached.

The beneficiary’s rights are always limited by the terms of the contract. A failure by the promisee to perform his part of the bargain will terminate the beneficiary’s rights if the promisee’s lapse terminates his own rights, absent language in the contract to the contrary .

Conferring rights on an intended beneficiary is relatively simple. Whether his rights can be modified or extinguished by subsequent agreement of the promisor and promisee is a more troublesome issue. The general rule is that the beneficiary’s rights may be altered as long as there has been no vesting of rights (the rights have not taken effect). The time at which the beneficiary’s rights vest differs among jurisdictions: some say immediately, some say when the beneficiary assents to the receipt of the contract right, some say the beneficiary’s rights don’t vest until she has detrimentally relied on the right. The Restatement says that unless the contract provides that its terms cannot be changed without the beneficiary’s consent, the parties may change or rescind the benefit unless the beneficiary has sued on the promise, has detrimentally relied, or has assented to the promise at the request of one of the parties. Some contracts provide that the benefit never vests; for example, standard insurance policies today reserve to the insured the right to substitute beneficiaries, to borrow against the policy, to assign it, and to surrender it for cash.

The general rule is that members of the public are only incidental beneficiaries of contracts made by the government with a contractor to do public works. It is not illogical to see a contract between the government and a company pledged to perform a service on behalf of the public as one creating rights in particular members of the public, but the consequences of such a view could be extremely costly because everyone has some interest in public works and government services.

A restaurant chain, hearing that the county was planning to build a bridge that would reroute commuter traffic, might decide to open a restaurant on one side of the bridge; if it let contracts for construction only to discover that the bridge was to be delayed or canceled, could it sue the county’s contractor? In general, the answer is that it cannot. A promisor under contract to the government is not liable for the consequential damages to a member of the public arising from its failure to perform (or from a faulty performance) unless the agreement specifically calls for such liability or unless the promisee (the government) would itself be liable and a suit directly against the promisor would be consistent with the contract terms and public policy. When the government retains control over litigation or settlement of claims, or when it is easy for the public to insure itself against loss, or when the number and amount of claims would be excessive, the courts are less likely to declare individuals to be intended beneficiaries. But the service to be provided can be so tailored to the needs of particular persons that it makes sense to view them as intended beneficiaries .

Kornblut v. Chevron Oil Co., 62 A.D.2d 831 (N.Y. 1978)

The plaintiff-respondent has recovered a judgment after a jury trial in the sum of $519,855.98 [about $2.6 million in 2024 dollars] including interest, costs and disbursements, against Chevron Oil Company (Chevron) and Lawrence Ettinger, Inc. (Ettinger) (hereafter collectively referred to as defendants) for damages arising from the death and injuries suffered by Fred Kornblut, her husband. The case went to the jury on the theory that the decedent was the third-party beneficiary of a contract between Chevron and the New York State Thruway Authority and a contract between Chevron and Ettinger.

On the afternoon of an extremely warm day in early August, 1970 the decedent was driving northward on the New York State Thruway. Near Sloatsburg, New York, at about 3:00 p.m., his automobile sustained a flat tire. At the time the decedent was accompanied by his wife and 12-year-old son. The decedent waited for assistance in the 92 degree temperature.

After about an hour a State Trooper, finding the disabled car, stopped and talked to the decedent. The trooper radioed Ettinger, which had the exclusive right to render service on the Thruway under an assignment of a contract between Chevron and the Thruway Authority. Thereafter, other State Troopers reported the disabled car and the decedent was told in each instance that he would receive assistance within 20 minutes.

Having not received any assistance by 6:00 p.m., the decedent attempted to change the tire himself. He finally succeeded, although he experienced difficulty and complained of chest pains to the point that his wife and son were compelled to lift the flat tire into the trunk of the automobile. The decedent drove the car to the next service area, where he was taken by ambulance to a hospital; his condition was later diagnosed as a myocardial infarction. He died 28 days later.

Plaintiff sued, inter alia, Chevron and Ettinger alleging in her complaint causes of action sounding in negligence and breach of contract. We need not consider the issue of negligence, since the Trial Judge instructed the jury only on the theory of breach of contract, and the plaintiff has recovered damages for wrongful death and the pain and suffering only on that theory.

We must look, then, to the terms of the contract sought to be enforced. Chevron agreed to provide “rapid and efficient roadside automotive service on a 24-hour basis from each gasoline service station facility for the areas…when informed by the authority or its police personnel of a disabled vehicle on the Thruway”. Chevron’s vehicles are required “to be used and operated in such a manner as will produce adequate service to the public, as determined in the authority’s sole judgment and discretion”. Chevron specifically covenanted that it would have “sufficient roadside automotive service vehicles, equipment and personnel to provide roadside automotive service to disabled vehicles within a maximum of thirty (30) minutes from the time a call is assigned to a service vehicle, subject to unavoidable delays due to extremely adverse weather conditions or traffic conditions.”…

In interpreting the contract, we must bear in mind the circumstances under which the parties bargained. The New York Thruway is a limited access toll highway, designed to move traffic at the highest legal speed, with the north and south lanes separated by green strips. Any disabled vehicle on the road impeding the flow of traffic may be a hazard and inconvenience to the other users. The income realized from tolls is generated from the expectation of the user that he will be able to travel swiftly and smoothly along the Thruway. Consequently, it is in the interest of the authority that disabled vehicles will be repaired or removed quickly to the end that any hazard and inconvenience will be minimized. Moreover, the design and purpose of the highway make difficult, if not impossible, the summoning of aid from garages not located on the Thruway. The movement of a large number of vehicles at high speed creates a risk to the operator of a vehicle who attempts to make his own repairs, as well as to the other users. These considerations clearly prompted the making of contracts with service organizations which would be located at points near in distance and time on the Thruway for the relief of distressed vehicles.

Thus, it is obvious that, although the authority had an interest in making provision for roadside calls through a contract, there was also a personal interest of the user served by the contract. Indeed, the contract provisions regulating the charges for calls and commanding refunds be paid directly to the user for overcharges, evince a protection and benefit extended to the user only. Hence, in the event of an overcharge, the user would be enabled to sue on the contract to obtain a recovery.…Here the contract contemplates an individual benefit for the breach running to the user.…

By choosing the theory of recovery based on contract, it became incumbent on the plaintiff to show that the injury was one which the defendants had reason to foresee as a probable result of the breach, under the ancient doctrine of Hadley v Baxendale [Citation], and the cases following it…in distinction to the requirement of proximate cause in tort actions.…

The death of the decedent on account of his exertion in the unusual heat of the midsummer day in changing the tire cannot be said to have been within the contemplation of the contracting parties as a reasonably foreseeable result of the failure of Chevron or its assignee to comply with the contract.…

The case comes down to this, then, in our view: though the decedent was the intended beneficiary to sue under certain provisions of the contract—such as the rate specified for services to be rendered—he was not the intended beneficiary to sue for consequential damages arising from personal injury because of a failure to render service promptly. Under these circumstances, the judgment must be reversed and the complaint dismissed, without costs or disbursements.

[Martuscello, J., concurred in the result but opined that the travelling public was not an intended beneficiary of the contract.]

Case questions