In 1817, James Monroe became the fifth President of the United States. He was the last Revolutionary War veteran and founding father to assume the Presidency. From an American Indian viewpoint, his presidential administration is important as it set the stage for Indian policies and for the administration of these policies which would guide the American government for two centuries.

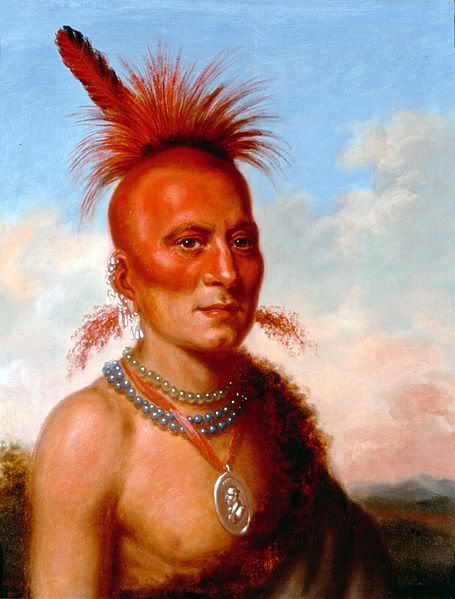

A portrait of President Monroe is shown above.

Monroe became President at a time when a new, sometimes fervent, nationalism was sweeping through the United States and this nationalism was also expressed in the handling of Indian affairs. In his first message to Congress, President Monroe stated:

“The hunter state can exist only in the vast uncultivated desert. It yields to the more dense and compact form and great force of civilized population; and of right it ought to yield, for the earth was given to mankind to support the greatest number of which it is capable, and no tribe of people have a right to withhold from the wants of others more than is necessary for their own support and comfort.”

President Monroe recommended that Indians who wanted to own land as individuals should be allowed to do so and should be given a fee simple title to their land. This would, of course, break up the communal land holdings of the tribes and allow “surplus” lands to be acquired and developed by non-Indians.

In 1824, President James Monroe presented Congress with a plan for “civilizing” Indians by sending them voluntarily west of the Mississippi River.

Meetings With Indians:

Following the Constitution and the precedent set by earlier Presidents, Indian tribes were viewed as sovereign nations and dealings with them often took on the trappings of international diplomacy. Indian leaders were often brought to Washington, D.C. so that they could be impressed with the size and power of the United States. As President, Monroe often met with Indian delegations.

In 1817, President James Monroe told a delegation from the Western Cherokee in Arkansas:

“As long as water flows, or grass grows upon the earth, or the sun rises to show your pathway, or you kindle your camp fires, so long shall you be protected by this Government, and never again removed from your present habitations.”

As with the promises of most Presidents, Monroe’s words would later prove to be false.

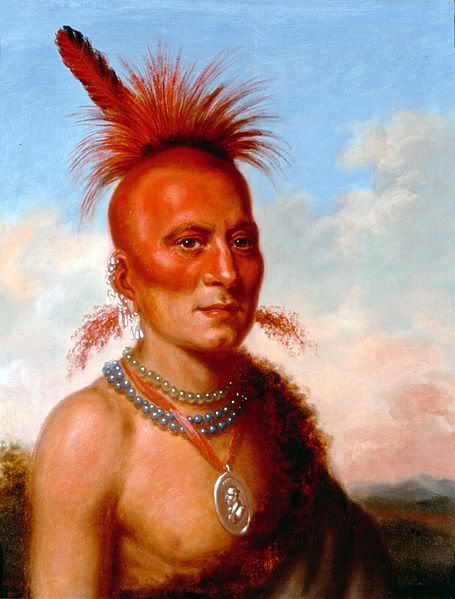

In 1821, Benjamin O’Fallon introduced a group of 17 Indian leaders to President James Monroe. The President told them that he hoped they would want the comforts of civilized life and that he was prepared to send them missionaries to teach their people agriculture and Christianity. Pawnee leader Sharitarish replied:

“We have everything we want-we have plenty of land, if you will keep your people off it.”

A delegation of Omaha from Nebraska under the leadership of Big Elk traveled to Washington, D.C. where they met with President James Monroe in 1822. Each of the Omaha chiefs had a portrait painted by Charles Bird King, a prominent artist.

Shown above is King’s portrait of Pawnee Chief Sharitarish done in 1822.

In 1824, the Cherokee Council sent a delegation to Washington, D.C. to talk with federal officials about their struggles with the state of Georgia. The delegates included John Ross, George Lowrey, Elijah Hicks, and Major Ridge. Over and over they told President James Monroe and other officials that the Cherokee would not cede any more land.

The Georgia delegation to Congress was outraged that the Cherokee were received with the same courtesy extended to foreign delegates. In their speeches to Congress, the Georgians called the Cherokee “savages” and accused the Cherokee of having a ghost writer to write their letters for them. However, the Cherokee dignity and good manners won them many admirers in Washington.

When the Cherokee delegation insisted that their annuity promised in the 1804 treaty had never been paid, President Monroe denied that such a treaty had ever been made. The Cherokee, however, produced a duplicate copy of the treaty signed by President Thomas Jefferson. After a search through the files of the War Department, the original treaty was found.

In addition to visiting the President, some Indian nations sought to contact him directly by mail. In 1819, the Stockbridge (who were now located in Indiana) wrote to President James Monroe to remind him of the service of their warriors on behalf of the United States during the Revolutionary War. They wrote that they had sent their warriors

“to join your great chief, Washington, to aid him in driving back into the sea the unnatural monsters who had come up from thence to devour you, and ravage the land which we a long time before granted to your fathers to live on.”

There is no indication that President Monroe replied to the letter or that he took any action in helping them.

Federal Indian Policies and Administration:

President Monroe appointed John C. Calhoun as Secretary of War and following the administrative procedures established by President George Washington this meant that Calhoun assumed the administrative responsibilities regarding Indian Affairs. As Secretary of War, Calhoun became the architect of a new Indian policy based on two principles: (1) the United States should preserve and civilize the Indians, and (2) the United States should not allow the Indians to control more land than they are able to cultivate.

As a part of the efforts to preserve Indians, in 1817 Calhoun requested that all Indian agents acquire “Indian Curiosities” for a cabinet of curiosities in the department. These curiosities were to include such things as moccasins, bows, skins, and items of Indian clothing.

In 1818 Secretary of War John Calhoun reported to the House of Representatives that the Indians west of the Mississippi River had become less warlike since their contact with Europeans. He proposed three basic changes to the aimless Indian policy of the past: (1) stop considering Indian tribes as nations, (2) seek to save Indians from extinction, and (3) inculcate among the tribes the concept of ownership of land. He stated:

“By a proper combination of force and persuasion, of punishment and rewards, they ought to be brought within the pales of law and civilization”. He also says: “The time seems to have arrived when our policy toward them should undergo an important change…Our views of their interest, and not their own, ought to govern them.”

With regard to the “civilized” tribes in the Southeast, such as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw, Calhoun recommended reducing their settlements to a reasonable size and moving them west of the Mississippi. Here they would be free from further demands on their lands by the United States.

Concerning education, Calhoun proposed compulsory attendance at schools for all Indian children. The government should provide the tribes with an annuity to fund the schools. He suggested that in the beginning these schools focus on vocational education until such time as Indians show an aptitude for the liberal arts. The first schools should concentrate on teaching agricultural techniques, homemaking, Christianity, and citizenship.

While Calhoun’s recommendations were ignored by Congress, they continued to guide the War Department in its dealings with Indians.

In 1819, Congress authorized an annual sum of $10,000 as a “civilizing fund” for Indians. The money was to be used to teach agriculture and to teach the children reading, writing, and arithmetic. Calhoun asked missionary societies to participate in this endeavor.

By 1824 there were 41 mission schools run by 11 missionary societies. Not including government funding (grants and annuity payments) these schools spent $170,606 on Indian education.

Calhoun established the Office of Indian Affairs (which would later become the Bureau of Indian Affairs) in 1824 without Congressional authorization. He did this by appointing Thomas L. McKenney to a vacant clerkship in the War Department and then having all matters relating to Indians directed through this office.

The Seneca, one of the members of the Iroquois League of Five (Six) Nations, had lived and farmed in New York for centuries prior to the creation of the United States. By the nineteenth century, land-hungry non-Indians wanted the Seneca land. In 1819, the Ogden Land Company, with the approval of the federal government, met with the Seneca to discuss buying their land. To watch out for the best interest of the Indians, the government appointed two agents to make sure that the Indians were not cheated or deceived. The Seneca chiefs-Little Billy, Red Jacket, Tall Chief, Young King, Two Skies, Infant, and Destroy Town-listened to the offer which was expressed in glowing terms about its benefit to the Seneca. One of the agents appointed by the government told the Seneca that President James Monroe felt it was in their best interest to sell their lands. The Seneca gave in and sold their land for 55 cents an acre and the land company quickly resold it for many times that amount. While the federal officials who oversaw the sale knew that the land was worth many times more than what the company paid for it, made no effort was made to insist that a fair market price be paid.

During Monroe’s Presidency, he was under a great deal of pressure from the Ogden Land Company to get the Iroquois nations in New York to sell their land and move to the west.

The Seminole:

During Monroe’s Presidency the United States engaged in the First Seminole War. The first Seminole War erupted in 1816 when the United States army, aided by Creek allies, invaded Spanish Florida. The rationale for the invasion centered around escaped slaves and Seminole raids. The war involved a series of raids and counter-raids and culminated with General Andrew Jackson’s scorched earth campaign against the Seminole. As a result of this war, the United States acquired Florida from Spain. At the conclusion of the war in 1824, President James Monroe recommended that the Seminole either be removed from Florida or placed on a reservation.